The S-WordWhenever a new acquaintance discovers that you homeschool, don't you cringe or stiffen just a little bit in anticipation of the question: What about socialization? Now more frequently asked with genuine interest (perhaps your interlocutor is considering homeschooling), occasionally with genuine concern for your children's wellbeing, irritatingly often with the air of "Here's why what you're doing is so wrong."

My favorite incident was the pediatrician who grilled me incessantly on why homeschooled kids couldn't be getting enough you-know-what, and she could never homeschool because (as she mentioned several times) her own child was so very social and friendly. Never mind the obnoxious implication that my own children must be introverted antisocial hermits; at the time of the interrogation, I was a captive audience in a hospital bed, having just had a c-section, trying to get an hours-old infant to latch on properly, and really not feeling up to the full-court defense being called for. Maybe she figured she only had a limited time to make sure I didn't repeat my awful educational mistake with this new child.

Volumes have been written on the s-word. Robert Reich, he of the mandatory two-week reeducation camps for homeschooled kids, is all about the s-word; he just has a fancy name ("ethical servility") and a theory that would permit government intrusion into the most private matters of personal belief and childrearing. But boiled down, it's just "they can't really be socialized, can they?"

No volumes here; just a few scattered thoughts that have occured to me over the years.

Invincible IgnoranceFirst, the odd phenomenon I like to call "invincible ignorance." An opponent of homeschooling tells you homeschooling is a bad idea because the children aren't socialized; kids have to be around other people. You answer with the usual raft of counter-examples; the zillion group activities your children are involved in, their close friends from the neighborhood or at church or in your hs'ing support group; their many friends and acquaintances of different ages whom they never would have met in an age-segregated school setting; their volunteer activities; the studies showing, on every conceivable measure, that homeschooled kids are at least as "socialized" as school kids. You thoroughly deconstruct the fantasy of the homeschooled kid slaving over textbooks at the kitchen table and gazing out the window at the happy busful of kids going off to school.

Your friendly foe nods throughout; sure, that's all probably true. "I still don't think," she says, when you've exhausted your ammo, "that it's good for kids to be so isolated. They need socialization."

Growing Up WeirdHere's another you've heard. "Kids need to be socialized or they grow up weird. My cousin's sister-in-law homeschools, and her kids are really messed up." The Argument from Weirdness shows up more and more often as homeschooling becomes more common. Okay, maybe our kids are a little weird. But let's remember that homeschoolers are self-selected for weirdness. This city, whose unofficial motto on a thousand bumper stickers is a clarion call for Weirdness, not coincidentally is renowned for its large and diverse homeschooling population.

Remember all the kids in your class who were weird? Some of them were weird and popular. Most of them were weird and weren't, and if you have a soul at all you felt sorry for them in school. So surely it will be a relief to think that a lot of them are being homeschooled now. The geeky brain who was bored all the time, the slow kid who never seemed to catch on, the fat kid who was withdrawn and wrote poetry a lot, the kid from a religious family who had to be excused from sex ed and from science class during the chapter on evolution and from P.E. when square dancing was being taught. Orthe kid with some medical condition or disability, not like the ubiquitous normal-looking "kid in a wheelchair" who shows up on every other page of modern textbooks to show that we never never discriminate, but was autistic or had psychological problems or was a burn victim. Remember how they were treated by the kids, and sometimes by the exasperated teacher?

Anyone whose first thought is "those are the kids who need to be in school getting socialized the most!" has forgotten what it's like to be a kid. Let's ask ourselves: did those same kids, in high school after a decade of "socialization," really seem much happier, better adjusted, and more popular?

At its best, the Argument from Weirdness forgets that kids and families that don't fit the mold are more likely to homeschool, so the strangeness of homeschooled kids isn't necessarily a result of not being in school. At its worst, it's a version of the "cut down the tall poppies" attitude that excuses inhumanity in the name of "making a man out of the lad" (a hundred yeas ago) or Mainstreaming to Promote Equity in Diversity (in today's ideologispeak).

And one last thought: what's

wrong with weird? If, as in the words of famed educator and Central Texan Peggy Hill, "being different is the most wonderful thing in the whole wide world," why do we Celebrate Diversity of the racial, ethnic, and orientative sort, but panic at the thought of kids growing up with diverse personalities?

E Pluribus UnumWhich brings us to the socialization-as-diversity-training argument. The popular form (which Reich has only refined to its inevitable totalitarian outcome) goes like this: In public school, kids will meet and interact with all sorts of different kinds of kids. Rich and poor, black and white and Asian and Hispanic, of various creeds and national origins, together in the great melting pot. Homeschooled kids don't get to do this, which is a disaster for civic polity.

My thoughts on how likely cultural diversity is to survive when the melting is forced, I've dwelt on before and won't repeat now. Instead let's look at two facts on the ground.

First, public schools aren't actually like that. My own public school experience was in a part of the country sometimes nicknamed "Silicon Gulch," where we were all living in suburbs newly carved from the Central Texas hills so our engineer parents could have an easy drive to work. "Diversity" was a matter of whether your parents worked for Motorola, IBM, or Texas Instruments. The schools were lily-white, with a sprinkling of Indian and Asian kids. In a city one-third Mexican-American and another third African-American, I never met a black or hispanic kid until college. When touring our highly rated local elementary school (in our consideration of options for Offspring #1), the landscape was the same that I remembered growing up: middle-class Anglo with some Asian and Indian. Turns out that our city, a blue speck in a sea of electoral red, is still one of the most segregated places in the country, with a redistricting of the schools a few years ago exacerbating the situation. Jonathan Kozol's recent book extensively examines the horrific de facto segregation of American schools by race and class.

Even where some ideal school with the lauded diversity exists, where did the idea come from that kids would come to respect and celebrate difference, growing up in harmony with others different from themselves? For Pete's sake, the preppies and the goths and the jocks won't even talk to each other. It's been a worry for years that, even when schools were less segregated due to busing, the black and white kids kept to themselves. Kids who might want to "cross the lines" of race, ethnicity, and money are held back by social pressure from the same large groups who are supposed to be "socializing" their age peers.

Second, the whole diversity argument depends on the obviously false assumption that homeschooled kids would by in public schools if not at home. But this is not the case: most would be in private or parochial schools if homeschooling were not an option. The "Christian Soldiers" family of the

New York Times article, meant to frighten mainstream America with their cultural isolation and high-octane religiosity, would, if homeschooling were outlawed, be in a small unaccredited Christian school with the other children of their little community. My crunchy-granola John Holtian friends would have their children in one of the several alternative progressive schools. My Catholic friends would be making the diocese miserable with their obtrusive and thoughtfully critical presence in the parochial schools. Unless we're prepared to shut down the private schools, or enforce mandatory state-sponsored diversity on them--which Reich's arguments would seem to require, and which the

Supreme Court has decisively nixed--it does no good to blame homeschooling for taking children out of the diverse public schools of our imaginings.

More to come....

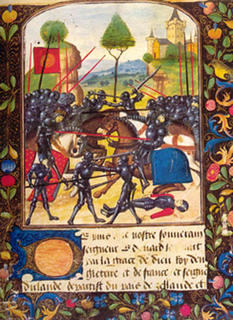

From The Golden Legend (1260):

From The Golden Legend (1260):